The new 6th Street Bridge in Los Angeles opened up on Sunday, July 10th, 2022. The bridge, with a $588 million dollar price tag, had a soft-opening without any vehicular traffic. Just pedestrians, bicyclists, skateboarders and others wanting to take in the spectacle of L.A.’s newest bridge. It was almost idyllic: the bridge opened up to people, not cars or the movement of commodities over the Los Angeles River.

The wild nighttime activity recently seen on the new bridge since its opening has almost been a mirror image of what the closing of the old bridge looked like: lowriders, taggers, public drinking, families enjoying the bridge one last time, fireworks and other revelry the night before the original 1932 bridge was slated for demolition.

The last night of the 1932 6th St. Bridge ended with the LAPD deploying riot squad for what was a boisterous, but peaceful crowd. The LAPD decided, as they often do, that escalation is the way to deal with its over-policed population.

Reactions to the wild nightlife on the bridge have been varied: some point out the worrying evidence that the bike lanes are not truly protected; others see the night revelers are merely doing it ‘”for the ‘gram”‘; some say “this is why we can’t have nice things”; others point out that the bridge is the result of local politicians further pushing gentrification ahead of the 2028 Olympics; and still others are saying this amounts to taking the bridge back.

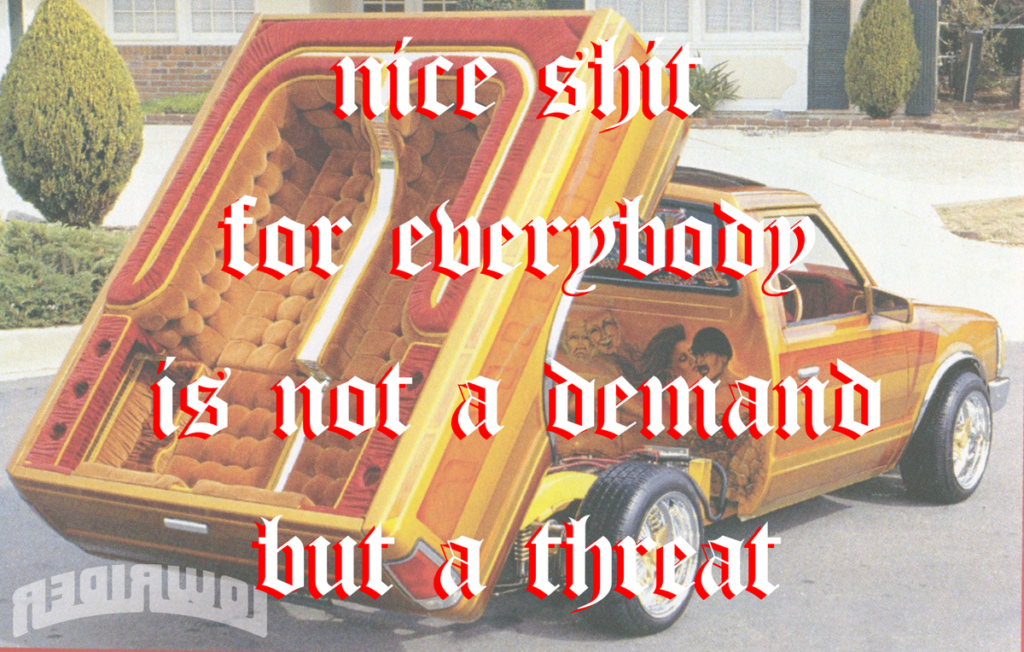

What I want to present here is an alternative radical position. One that is influenced by the works of the Situationist International (namely, psycho-geography) and also influenced by the influence of Mexican-American rasquache as seen here in the greater so-called Los Angeles area.

It’s easy to dismiss the night revelers as merely performing all their stunts for social media. In the age of Instagram & TikTok, this cannot be dismissed but this is an ahistorical take which retroactively assumes that without social media, night revelry would not exist. The city of Los Angeles has had a long history of night revelry.

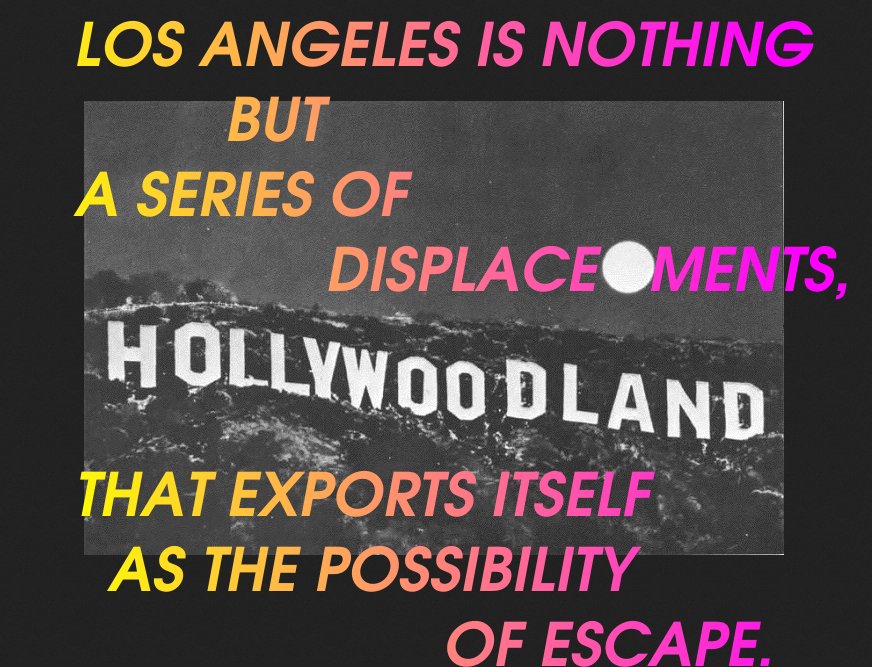

Public space has always been contentious in Los Angeles. The old school socialist Mike Davis dubbed this city, “Fortress Los Angeles”: after all for the way the city has been largely fortified and secured to ensure the daily reproduction of capitalist social relations at the expense of everything and everyone else. Social life that is not seen as perpetuating this capitalist way of life are stamped out. This can be easily seen in contemporary Los Angeles where fruit carts, taco trucks & night markets are incredibly popular, locally & internationally, but because they do not square with the strict formal legalism of the city, they are shutdown or repressed. Kelly Lytle Hernández, in her book on the social history of incarceration in Los Angeles, “City of Inmates,” notes how part of the settling and colonization of native Tongva land was the elimination of the Tongva, and other local Native peoples, from public space by essentially making their non-working presence in public spaces illegal.

“…the Californios of Los Angeles had concerns about the growing number of Indigenous peoples living in and around Los Angeles. Too many indios, they complained, spent their days playing peon (gambling), at the village or drinking in grog shops near the plaza. According to Californios, who had carefully organized the local culture and economy around Native labor, there was no place for Natives living but not working in Mexican Los Angeles. In turn the ayuntamiento (city council) passed new laws to compel Natives to work, or be arrested. In January, 1836, the ayuntamiento required all Californios to sweep across the town every Sunday to arrest ‘all drunken indians.’ The alcalde (mayor) required all those arrested to pay a fine or be subject to forced labor on public works projects.” (Kelly Lytle Hernández, City of Inmates)

Later in the book Kelly L. Hernández points out how this forced prison labor became a major source of labor for the city of Los Angeles and many of the major streets in the city were created by forced prison labor. The city is marked by historical & present State policies of segregation and elimination of undesirables.

As a young Mexican-American kid growing up in this city in the 80s & 90s, being in & using public space always felt like a constant war with the police (& other private security apparatuses). Any real venues or clubs were too expensive or would not cater to the Eastside punk scene I was a part of (or simply would not want us.) And in this constant war with the police over public space, spaces which were never meant to be opened-up or transformed become the places where young, especially racialized Angelenos gather.

We would gather on undeveloped hillsides, under bridges, in the Los Angeles River cement bed, downtown when it would get largely abandoned at night in the past, in abandoned houses or in empty warehouses that de-industrialization left in its wake. What is happening on the bridge is nothing new. Within Fortress L.A., there has also always been a running current Columpio Los Angeles, or “Playground Los Angeles”: racialized proles have always carved out their own spaces out of necessity . And because there is a lack of ready-made public space, time becomes a factor: the city se pone cabrón at night.

Of course this true of most cities with a rowdy racialized prole population: the street takovers; the illegal raves; the backyard parties; the flyer parties at abandoned mansions; the boulevard cruising and of course .

The night revelers are also re-introducing play to a city whose social life largely collapsed during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. And with ever-rising inflation, rents that keep spiking and with diminished savings, racialized proles are looking for a way to spend their so-called free time, or leisure time. But here is where the problem arises for the city of Los Angeles. Ostensibly the “entertainment capital of the world”, most of the ways the city expects you to “enjoy yourself” are not cheap nor accessible to all.

“When freedom is practised in a closed circle, it fades into a dream, becomes a mere image of itself. The ambiance of play is by nature unstable. At any moment, “ordinary life” may prevail once again. The geographical limitation of play is even more striking than its temporal limitation. Every game takes place within the boundaries of its own spatial domain.” — Guy Debord, from his film “” (1959).

This does not mean that play is not without its risks. Climbing on the arches of the new 6th St. Bridge is dangerous and car crashes are dangerous. But the whole city is a hazard unto those who live and work here. What is frightening for authorities is a wild, revelrous, playful chusma (Spanish, for riff-raff) that breaks with the regime of work: where a bridge meant to facilitate the movement of commodities (whether goods or labor-power), loses its original purpose and becomes a playground for those the city has worked to eliminate. Already there are plans to to clamp down on extra-legal activity.

Los Angeles politicians involved with the bridge project often said they wanted the bridge to become a “destination”, but their intention was likely not to become a persistently reclaimed public space in the shape of a bridge.

An interesting historical parallelism happened recently on the bridge as well. Almost 48 years ago, the Mexican-American art group ASCO, took to a street medium to host what they called “First Supper (After a Major Riot)” in 1974, technically on Atlantic Blvd but the Whittier Blvd sign is clearly, and intentionally visible.

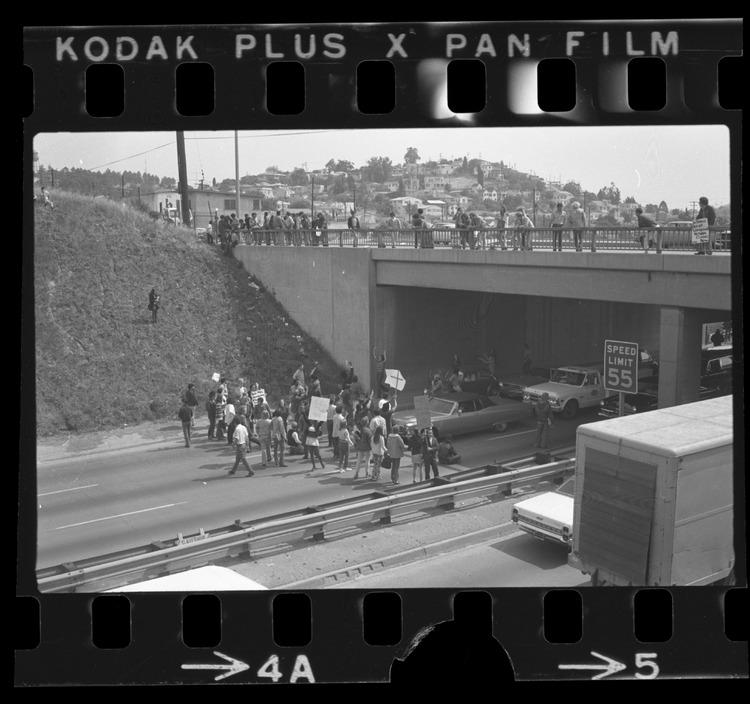

The photo was a commemoration of a large anti-Vietnam draft demonstration that turned into . In 2022, a young barber from North Hills bought a chair and decided, on a whim, to post up on the 6th St. Bridge and give out haircuts. Whittier Blvd turns into 6th St near the bridge.

The intentions may be wildly different for both, but there is a historical continuity here where to affect and get attention from the city, one has to put oneself in harm’s way and in traffic. An echo of the freeway takeover.

The amount of creative re-purposing of the bridge grow each day: a dangerous barber shop; a stage for an impromptu parachute jump; parkour; a good spot to smoke; a new spot for fresh new tags; a venue for a corrido band, a backdrop for a quinceañera photoshoot… the list will only continue to grow. This is how public space has always been in this city where the only activities deemed appropriate are ones which perpetuate Los Angeles as a site of the production & circulation of commodities under settler rule.

It is via this creative (& at times destructive) interplay with the very architecture, the very infrastructure of the city which changes and has changed the very fabric of the city. It’s an embodiment of “” where racialized proles take what was not created for them, and what was not intended for them, but they take it all the same. The multi-trillion film & television industry can shut down whole Los Angeles bridges regularly with no problems but as soon as some everyday Los Angelenos start realizing the joy they want to live, the city will shut down the bridge.

As of today, July 27th 2022, the bridge has been open for a little over two weeks and . One almost wonder if they’ll start to have toll booths & check points to keep the Los Angeles chusma away.

¡ Qué viva la chusma y la realización de la alegría en la vida cotidiana !

c/s – noche

A rola to bump in your ranfla as you cross the 6th St. Bridge.